Archive for April, 2024

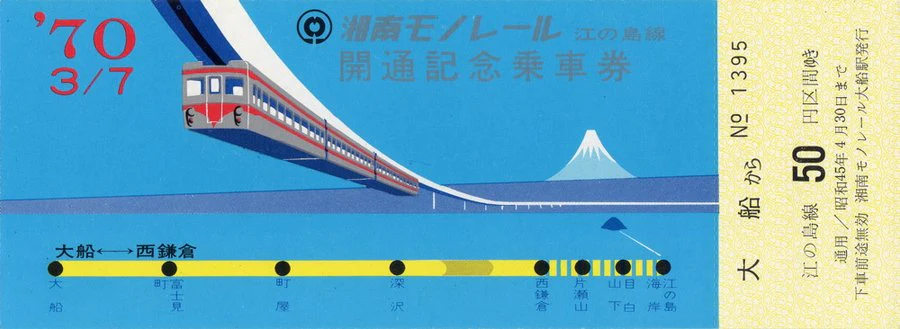

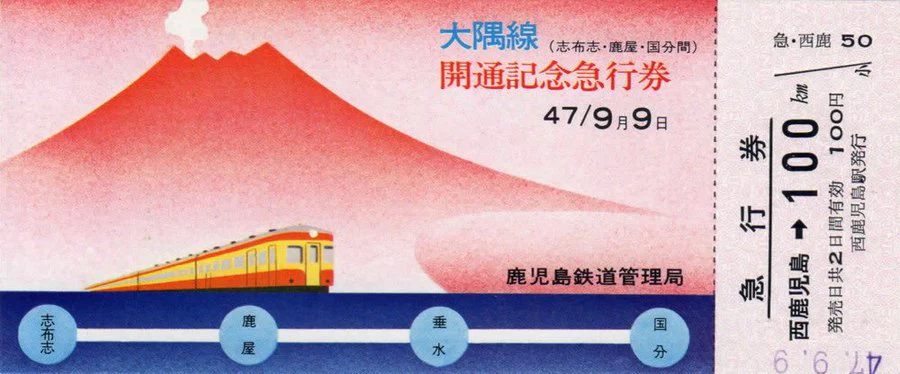

Japanese Train Tickets

Present & Correct has assembled some stunning train tickets from Japan into one little gallery. So good.

Via Kottke

Apple Jonathan

My day job as a designer of Mac apps gives me a special fondness for computer concepts. This is a little-known Apple prototype from the 80’s which was a candidate to be a new platform alongside, or instead of, the Mac. Inspired by a bookshelf, “This concept envisioned a computer that would expand with the needs of the user, through the use of modular components”.

The user would add modules depending on what they needed to do, like disk, drives, storage, video cards, or specialized components. Modular designs often work out better in theory than in practice, and it’s likely that in this case getting all the pieces to work with each other would have been a technical nightmare.

Via Daring Fireball

On School Start Times, ADHD, and Sleep

I’m currently looking into high schools for my son, and start times are playing a larger role than expected. Many are too early for us to be able to get there on time without waking at an unreasonable hour. According to sleep researcher Dr. Matthew Walker, early school start times are increasingly common, as he writes in his book Why We Sleep:

A century ago, schools in the US started at nine a.m. As a result, 95 percent of all children woke up without an alarm clock. Now, the inverse is true, caused by the incessant marching back of school start times—which are in direct conflict with children’s evolutionarily preprogrammed need to be asleep during these precious, REM-sleep-rich morning hours.

Many schools start at 8:00am, or sometimes even earlier. Some of these otherwise great schools have dropped far down our list because of their unreasonable start times.

Levels of ADHD have been rising steadily around the world. This might seem unrelated, but according to Walker, sleep deprivation symptoms are often indistinguishable from those of ADHD.

If you make a composite of these [ADHD] symptoms (unable to maintain focus and attention, deficient learning, behaviorally difficult, with mental health instability), and then strip away the label of ADHD, these symptoms are strongly overlapping with those caused by a lack of sleep. Take an under-slept child to a doctor and describe these symptoms without mentioning the lack of sleep, which is not uncommon, and what would you imagine the doctor is diagnosing the child with, and medicating them for? Not deficient sleep, but ADHD.

More research is needed, as correlation does not mean causation, but the possibility that some of the rise in ADHD can be attributed to early school times is intriguing. As someone who is both bad at sleep, and diagnosed with ADHD, these passages are making me think hard about my own experiences in childhood with ADHD medication, which I absolutely hated and stopped after a couple of days.

Montreal Murals

Montréal has seen many, many pieces of public art pop up in the last few years, thanks in part to the Mural festival. These artworks are accessible, free to the public, and take art out of the institutional (dare I say elitist) art galleries. The city has started to curate a photo gallery of these murals, which number over 300(!). Worth a scroll to see some great pieces.

Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows

Maria Popova’s excellent Marginalian blog shared some excerpts from John Koenig’s 2021 book The Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows, for which the author created new words to describe types of malaise for which don’t have current English words for. For example:

AGNOSTHESIA

n. the state of not knowing how you really feel about something, which forces you to sift through clues hidden in your own behavior, as if you were some other person — noticing a twist of acid in your voice, an obscene amount of effort you put into something trifling, or an inexplicable weight on your shoulders that makes it difficult to get out of bed.

Via Rafa

Your Undivided Attention on Social Media and Youth

As someone who is quite solidly anti-social media (this blog is the closest I come to taking part in social media), this episode of the Your Undivided Attention podcast is a sobering listen. It’s an interview with writer Jonathan Haidt, where they particularly focus on the mental health crisis among Gen Z, the first generation who have grown up completely in the social media era. Notably, Zoomers have much higher rates of anxiety and depression.

It starts with a sobering detailing of a slow educational crisis starting with Ben Z (generally considered to be kids born from the mid/late 90’s into the early 2010’s):

…humans had a play-based childhood for millions of years because that’s what mammals do. All mammals play. They have to play to wire up their brains. But that play-based childhood began to fade out in the 1980s in the United States and it was gone by 2010, and that’s because right around 2010 is when the phone based childhood sweeps in…

…scores in math and reading and those were all fairly steady, and then all of a sudden, after 2012, they drop. So that’s international. Around the world, our young people are… not learning as much as they would have a few years before.

Yuri-G

A classic banger from Polly Jean Harvey, for the anniversary of Yuri Gagarin going into space for the first time.

Taking 'Green' Out of the 'Green Screen'

Until the age of about 14 I was certain I wanted to do movie special effects when I got old enough. Plans changed, but I still enjoy watching how special effects are done. In this case, a small studio resurrected a decades-old technique for making a “green screen” effect using sodium vapour lighting and prisms. Neat!

Review of Every Living Thing

Friend of Elsewhat Jason Roberts has a new book, out yesterday, called Every Living Thing. His last book, A Sense of the World was beautiful and amazingly well researched, making this an instant buy (from your local independent book store, not Amazon).

The book follows the paths of two scientists endeavouring to come up with a taxonomy system to classify, well, every living thing. From the New York Time’s review:

Roberts’s exploration centers on the competing work of Linnaeus and another scientific pioneer, the French mathematician and naturalist Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon. Of the two, Linnaeus is far better known today. Of course, Roberts notes, the Frenchman did not pursue fame as ardently as did his Swedish rival. Linnaeus cultivated admiration to a near-religious degree; he liked to describe even obscure students like Rolander as “apostles.” Buffon, in his time even more famous as a brilliant mathematician, scholar and theorist, preferred debate over adulation, dismissing public praise as “a vain and deceitful phantom.”

Their different approaches to stardom may partly explain why we remember one better than we do the other. But perhaps their most important difference — one that forms the central question of Roberts’s book — can be found in their sharply opposing ideas on how to best impose order on the planet’s tangle of species.