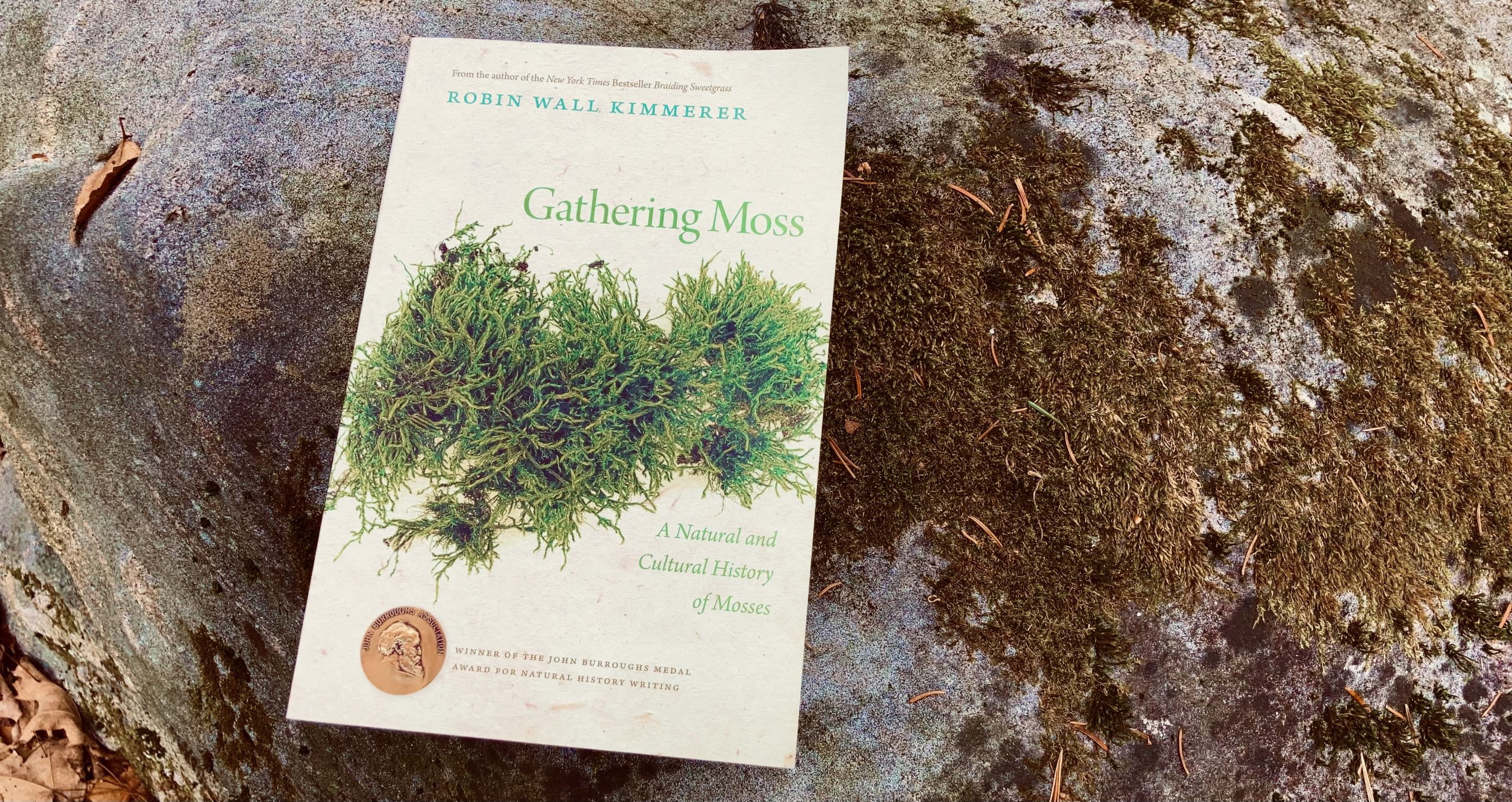

A couple of years after reading Robin Wall Kimmerer‘s Braiding Sweetgrass, I returned back to her 2003 debut non-fiction book Gathering Moss. Kimmerer is a Bryologist, or someone who studies moss. This short book gives an overview of these under appreciated organisms. Mosses don’t tend to get the sort of love or attention larger plants get. Kimmerer writes:

We carefully catalog the positions of all the moss species, calling out their names. Dicranum scoparium. Plagiothecium denticulatum. The student struggling to record all this begs for shorter names. But mosses don’t usually have common names, for no one has bothered with them. They have only scientific names, conferred with legalistic formality according to protocol set up by Carolus Linnaeus, the great plant taxonomist. Even his own name, Carl Linne, the name his Swedish mother had given him, was Latinized in the interest of science.

Her book explores many, many facets of mosses, from how they reproduce, to how peat bogs are formed. As in Braiding Sweetgrass, she also brings a perspective that blends science with an indigenous point of view. For example, this section where she describes her experience trying to figure out why a certain moss reproduces in a counterintuitive way:

But if there’s anything that I’ve learned from the woods, it’s that there is no pattern without a meaning. To find it, I needed to try and see like a moss and not like a human.

In traditional indigenous communities, learning takes a form very different from that in the American public education system. Children learn by watching, by listening, and by experience. They are expected to learn from all members of the community, human and non. To ask a direct question is often considered rude. Knowledge cannot be taken; it must instead be given. Knowledge is bestowed by a teacher only when the student is ready to receive it. Much learning takes place by patient observation, discerning pattern and its meaning by experience. It is understood that there are many versions of truth, and that each reality may be true for each teller. It’s important to understand the perspective of each source of knowledge. The scientific method I was taught in school is like asking a direct question, disrespectfully demanding knowledge rather than waiting for it to be revealed.

A+