The first time I heard about language-based AIs, I was sitting in a beautiful Montréal park, and friend of Elsewhat Sean started talking about what AI could do with language. This was years before GPT got its “chat” prefix and became the sensation it has since become. I remember being baffled by hearing about GPT could take long strings of text and near-instantly rewrite them in a different style, or summarized shorter, or expanded, or just write from scratch. I felt somewhat in awe of the description of this technology, which took a few more years to go mainstream, but the impression he gave was that this was going to have a big impact on society.

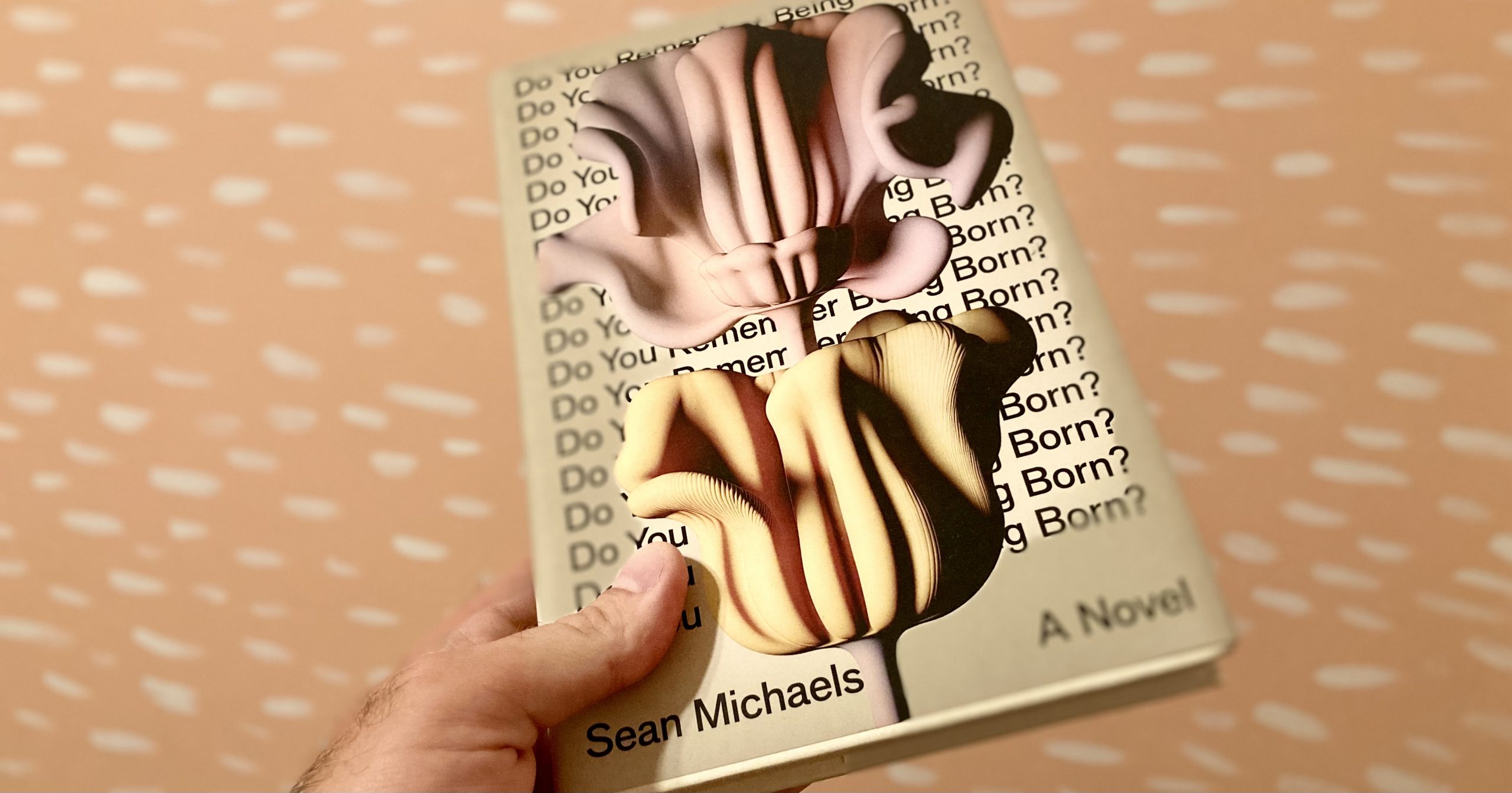

Sean was then, and continues to be, way in advance of other artists in his understanding, and use of AI. This novel, years and years in the making, is testament to that. It feels like it could not be timed any better—Right as people are discussing what AI will do to art, here comes a beautiful book about, and partially written by AI.

The book follows a successful poet in her mid-seventies, Marian Ffarmer, as she’s commissioned by a California big-tech company to collaboratively write a piece of poetry with the company’s cutting edge language-based AI, Charlotte. Marian is a beautifully rendered character, and her eccentric, mischievous manner makes her a perfect foil to the polished technocrats at the big California computer company.

This book is excellent, and a very timely contribution to the debate on how AI impacts art. The New York Times gave a glowing review, and I agree. This is a thoughtful work, which simultaneously looks back at the long life of an artist as she navigates a new technology, created in a few short years, which will forever change the craft she’s taken her lifetime to master.

It’s also, importantly, not a work that tries to predict the long arc of where the technology will go, or the possible impacts it might have on society. It’s foremost about the artist, and her act of using tech in creating something which was, until now, quintessentially human.

Buy the Book (Canada) →

Buy the Book (US) →